The Psychology of Success: Growth Mindset vs. Fixed Mindset

Psychology is defined as the scientific study of the mind and behavior. It examines how people think, feel, perceive, learn, remember, and act, both as individuals and in groups. The psychology of success is the study of the mental processes, traits, and behaviors that enable individuals to achieve their goals and sustain high performance. It examines how thoughts, emotions, motivations, and self‑perceptions influence the pursuit and attainment of success in various domains (academic, professional, personal, etc.).

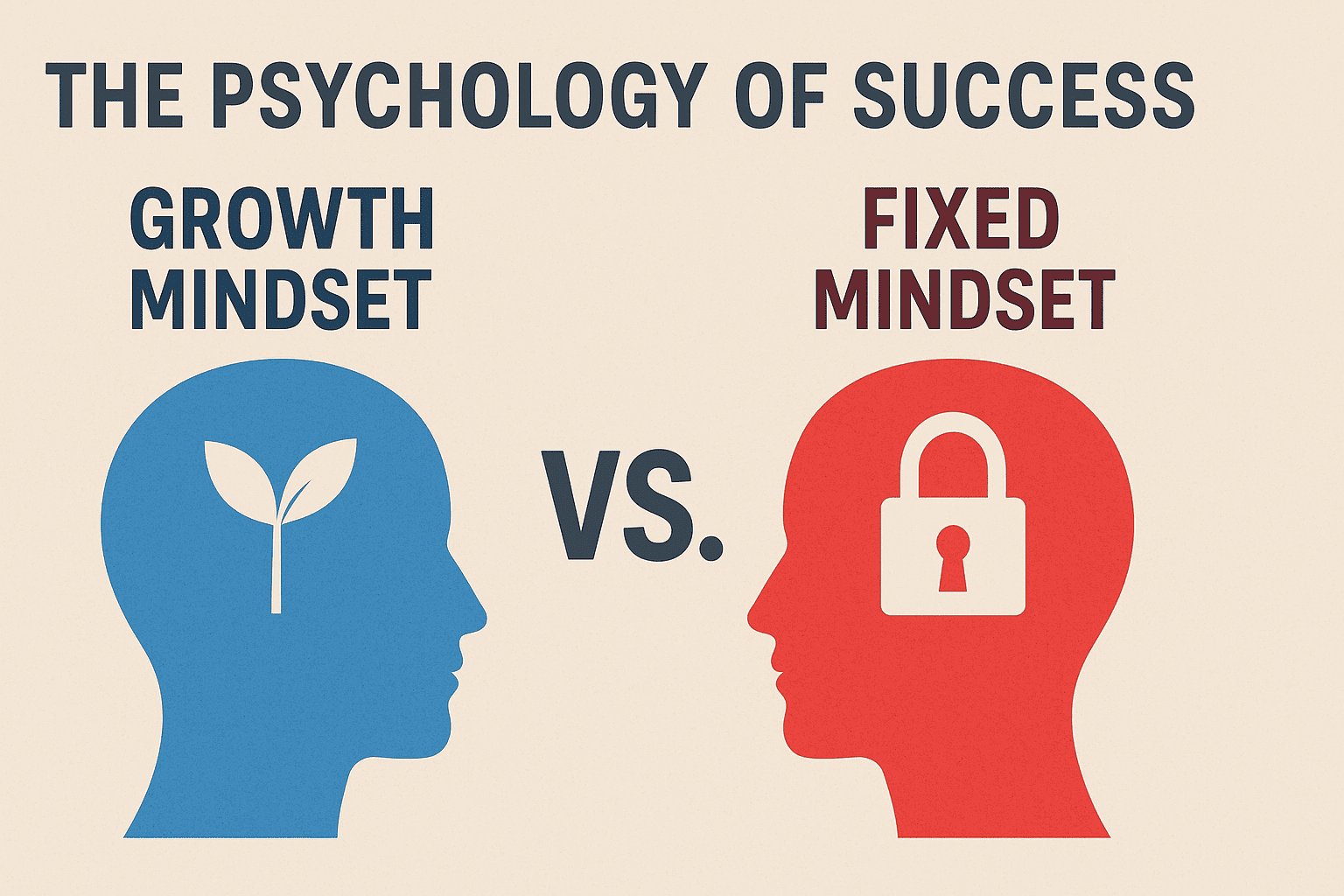

Carol Dweck’s decades of research show that the way we view intelligence and talent dramatically shapes how we learn, perform, and ultimately succeed. She identified two fundamental mindsets namely:

Growth Mindset: A belief that abilities and intelligence can be developed through effort, learning, and persistence. People with a growth mindset view challenges as opportunities, see failure as a stepping‑stone to improvement, and are motivated by progress rather than just innate talent.

Fixed Mindset: A belief that abilities and intelligence are static traits that cannot be changed. Individuals with a fixed mindset tend to avoid challenges, see failure as a reflection of their inherent worth, and often seek validation through proving their existing abilities.

Aspect | Fixed Mindset | Growth Mindset |

Belief about abilities | Abilities are static (“I’m just not a math person”) | Abilities can be developed through effort and learning |

Reaction to challenge | Avoids challenges (fear of failure = proof of lack of talent) | Embraces challenges (opportunity to grow) |

Response to obstacles | Gives up easily | Persists longer |

Effort | Sees effort as fruitless (if you’re talented, you shouldn’t need it) | sees effort as the path to mastery |

Criticism | Ignores or gets defensive | Learns from criticism |

Success of others | Feels threatened (comparison) | Finds inspiration and lessons |

Result | Plateau early, achieve less than potential | Continuous improvement, higher achievement over time |

Real-World Consequences (Dweck’s Key Studies)

- The “Puzzle Study” with children: Kids who were praised for intelligence (“You’re so smart!”) chose easier puzzles next time to protect the “smart” label.

Kids praised for effort (“You worked really hard!”) chose harder puzzles becaue they saw challenge as fun and growth-producing.

- Longitudinal studies in schools: Students who entered middle school with a fixed mindset saw steady declines in grades when coursework got tough. Students taught (in just 8 sessions) that the brain is like a muscle that grows with use reversed the decline and outperformed peers.

- Professional sports & businessFixed-mindset CEOs are more likely to cheat after setbacks (Enron-style scandals).Growth-mindset leaders (e.g., Satya Nadella at Microsoft, Anjali Sud at Vimeo) turned struggling companies around by fostering learning cultures.

Brain Science Behind It (Neuroplasticity)

Modern neuroscience confirms Dweck’s work:

When you struggle and persist, your brain forms new connections (myelinates pathways).

Fixed-mindset individuals show heightened amygdala (fear) response to errors.

Growth-mindset individuals show activation in learning and error-correction regions (prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate).

How to Cultivate a Growth Mindset (Practical Tools)

- Change your language Fixed → Growth “I failed” → “I learned” “I’m bad at this” → “I’m not good at this yet” “This is too hard” → “This will take some time and effort”

- Add the word “Yet” (the most powerful three-letter word in psychology) “I don’t understand calculus… yet.”

- Praise process, not person Instead of “You’re a natural genius,” say: “I loved watching how you kept trying different strategies.”

- Reframe setbacks as data After a failure, ask:

What went well?

What could I do differently next time?

Who has succeeded at this that I can learn from?

- Teach the brain is a muscle metaphor One semester-long intervention using this metaphor raised students’ math grades by an average of 0.5 grade points and cut behavioral referrals in half.

Famous Examples

7UP is the ultimate cockroach brand with ugly history, kicked around, reformulated into oblivion multiple times, yet it refuses to die.

Michael Jordan cut from varsity as a sophomore → practiced obsessively (growth).

Thomas Edison 10,000 “failures” before the light bulb → “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

J.K. Rowling 12 publisher rejections → used feedback to improve Harry Potter.

Warning: The False Growth Mindset

Many people say “I have a growth mindset” but still:

Avoid real challenge

Collapse at the first setback

Use “effort” as a consolation prize instead of a strategy

True growth mindset isn’t blind positivity; it’s the belief that effort + good strategies + help from others = improvement.

Quick Diagnostic (Answer honestly)

- When you fail at something important, do you tend to feel it reveals you lack ability?

- Do you avoid tasks where you might not immediately excel?

- Do you feel threatened when a peer outperforms you?

The more “yes” answers, the more fixed your mindset may be in that domain and the bigger the opportunity for transformation.

Dweck’s ultimate finding: Success is less about initial talent and more about how you interpret and respond to difficulty. The mindset you adopt becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

References

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Dweck, C. S. (2016). Mindset: The new psychology of success success (Updated ed.). Ballantine Books. (Original work published 2006)

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000794